John Waters is the worst: how his humor shows us our own absurdity at Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco

The "Sultan of Sleaze" takes viewers on a journey of laughs and life lessons. Written by Cole Hersey for Variable West.

John Waters’s work is often described as grotesque—he is the “Sultan of Sleaze” after all—but there is something maniacally beautiful and intriguing in how his work can revile while it also uplifts. His work is about perspective. Absurd and joyful, Waters knows how to provoke discomfort for those within the norms of polite society. His work lives within that jostling, with his own joy and laughter against the stern perspectives of onlookers, of forcing something fun and wild in the face of viewers. He always wants to provoke, often in a manner that quips not only at the viewer, but Waters himself.

Most importantly, it is Waters’s use of humor that provokes this play with perspective. It is his ability to mock everything and take true pleasure from it that makes his work a wonderful and weird joy to see. His recent exhibition, The Worst of Waters, on view at Rena Bransten Gallery at Minnesota Street Project in San Francisco September 21 – November 16, 2024, was no different.

The show is a series of appropriated movie stills and photographs, some old sketchbook drawings and notes. The images in the exhibition—everything from anal examinations, a series of a man appearing to moan, a film still of a shirtless Stud (1998)—are idyllically uncanny, making the viewer laugh and cringe in turn. It’s fun and beautiful. However, the major push of it all is to make light of ourselves, Waters included, for enjoying this kind of insanity, for partaking in the ludicrousness of convention and of media and the arts more generally.

Upon entering the gallery, visitors immediately see the Bad Director’s Chair (2006) with silkscreen phrases and insults covering it such as “HACK.” Moving through photos of people vomiting and in various states of discomfort, it seemed that Waters intended for us to be in a state of reviled wonder, for how oddly the humor of each piece stood in contrast to much of the work’s content. After passing through the images in the gallery, visitors are met with a screen where little kids perform a G-rated version of Pink Flamingo called Kiddie Flamingo (2014).

Most of the stills in the show share a twisted authenticity that these films were hoping to avoid. Waters is pointing out that those of us who partake in this weird polite performance of art viewing are ourselves just as unknowing and silly and crude as the subjects in these images. How ridiculous all of this is, Waters seems to say.

According to a press release, the show is “a hit parade of hell, Waters’s photographic prints and sculptures use appropriated movie imagery that both mocks and embraces the extremes of the art world and show business all in one whoop of demented joy.”

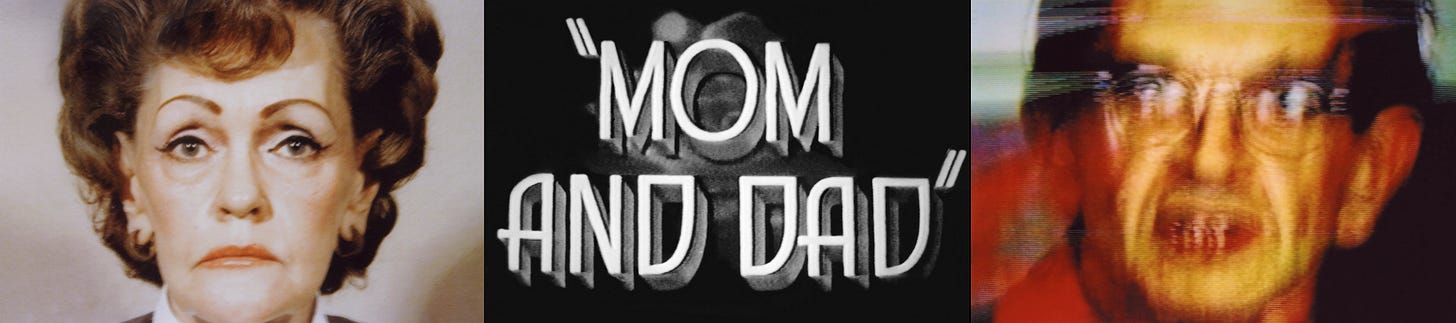

Mom and Dad (2014) presents a triptych of film stills showing a woman in her sixties with plenty of make-up, staring desperately into the camera. Opposite this scene, a man is mid-speech and almost angry, his face distorted either from his movement or the camera’s. In the middle, a bold gray font reminiscent of a 1950s PSA reads “Mom and Dad.” It appears like a depiction of an undercurrent of fear and subordination during the nuclear family boom. It made me feel uncomfortable and confused the more I looked at their faces. But, in the same way we view this piece, we view film and media at large—taking in subtle cultural queues until it’s hard for us at times to remember what might be innate, and what might be convention.

The images in the show share a rawness that most of these films were possibly hoping to avoid. All of us, Waters seems to be saying, who partake in this weird and strange kind of performance of art viewing are ourselves just as ridiculous, just as fake, as bad, as silly and unknowing as all the characters in these images, like those hapless people vomiting in the film stills that make up Puke In The Cinema (1998).

This exhibition is a playful romp. Each piece is a confrontation with the desire to be viewed, and how that viewing can turn awry. Waters is pointing out how funny this confrontation is, and making us certain through his absurdity of how little all this really matters.

Almost every piece, for different reasons, initially made me laugh. For instance, the photo collage Cancel Ansel (2014) is composed of Ansel Adams images superimposed with odd additions like a cruise ship in Yosemite Valley. Others were made to have a plane crashing over clear mountains, or a flamingo perched on a twisted bristlecone pine. These colleges mock the thorough urbanization of these theoretically wild National Parks. There was also Hairball (2014), a collage piece showing five men’s hairy chests beside an ad image for a “chest wig.” Sexual Attraction (2014) showing pictures of two people with slanted grins between an illustration of some internal organs, or the simply titled Pimples (1998), which shows a series of images of pimple-ridden faces.

I’m not certain where the images come from, and I’m not so sure it truly matters, just that they were out there, in some form, part of the mass of images we’ve been obsessively creating for the past hundred or so years. Waters only brings these to our attention to make us laugh at how wild it is to be alive in this era.

The work is absurd in nature because what other work can you make in the world today? This is the reason his work, which originally made him into a provocative celebrity, is being admired and rightly canonized today. He’s so comfortable with living in the insanity of our world and his own. And while Marvel movies try to play at this with the likes of Deadpool (2016) and its breaks in the 4th wall, few are able to capture a truthful depiction of the absurdity of our lives quite like Waters.

John Waters: The Worst of Waters

Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA

September 21, 2024 to November 16, 2024